by John Ellis

(Edit on 8/19/25: I’m currently rereading Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts by Marx and realized that I made a small error. Marx didn’t believe that communism was necessarily the final stage for humans. He believed that it was impossible to know when/what the final stage, if there ever is one, will be. So, my direct comparison of communism with Christian eschatology isn’t totally correct. I don’t believe that this undermines my thesis, though, because it doesn’t change Lenin’s error.)

While a student at Bob Jones University, I was desperate to remove myself as ideologically as far away from Christianity as possible but not quite sure how. To help solve my problem I sought after literature that could help me find my intellectual footing as an anti-Christian. Ironically, a BJU lit class introduced me to Letters from Earth and Extracts from Adam’s Diary, both penned by Mark Twain. Longing for more, I stumbled across Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian in a Barnes & Noble. That book then led to me to Roads to Freedom: Socialism, Anarchism and Syndicalism, also by Russell. I discovered it in BJU’s Mack Library, checked it out, and then never returned it (stole it).[1]

Look, I’ll be honest, it’s been years, decades even, since I last read Roads to Freedom. In my hazy recollection, I don’t recall it being an overly dogmatic pro-Marxist screed. If I remember correctly, and based on a quick glance at the back cover, the book is a general description and comparison of various forms of socialism ending with Russell’s belief for what economic system/form of government would best serve a post-WWI world. Regardless of what’s in the book, it was the genesis of my becoming a Marxist. Well, not so much a Marxist but someone who really really wanted to be a Marxist but didn’t actually understand it apart from believing it was the exact opposite of being a Republican. Seeing as how my parents, along with every other person in my Christian fundamentalist upbringing, were Republicans, Marxism seemed the best option.

To be fair, I also read The Communist Manifesto while I was a student at BJU, and think I even understood parts of it. But a Marxist I was not, even while proudly telling everyone I was. It’s similar to how, prior to my conversion to Marxism, I spent a few months telling people I was Taoist after I had read The Tao of Pooh.[2]

Right, so, fast forward to 2025 and I no longer identify as a Marxist (although some of my critics believe otherwise). I guess it’s ironic that I would make a better Marxist now than when I believed I was one because I now understand Marxism way better than I did in the late 90s and early 00s.[3] And armed with that understanding of Marxism (and the history of the Soviet Union) I confidently assert this thesis: Christian nationalists share with Lenin a perverted eschatology of their respective professed faiths. Here’s what I mean.

One of my bugaboos is the colloquial use of terms like begging the question. When people say, “that begs the question” they almost always mean “that raises the question.” They (usually) aren’t pointing out the existence of a circular argument. My pedantic annoyance is tempered, publicly at least, by my understanding of how communication works. When someone says “that begs the question” in front of me, I know what they mean; I don’t presume that they are, indeed, pointing out a logical fallacy. So, I resist the urge to correct them (out loud). The same is true when people use the term communism. I will add that the colloquial definition of communism is so entrenched in our societal lexicon as to be the correct definition now, as much as I may wish otherwise. The problem with this evolution in the word’s meaning is that it does make it harder to understand Marxism because terms have become confusedly conflated.[4] For my purposes, I’m going to do my best to use the terms as Marx would’ve understood them. So, ….

The overwhelming majority of the time, communism is used incorrectly as a synonym for Marxism. In actuality, communism is the term that describes Marx’s eschatology. Calling a Marxist a communist is like referring to Christians as Heavenites or, more theologically accurate, New Earthers which sounds really close to flat earthers so I’m opposed to that colloquially linguistic switch on multiple levels.

One of the most important tenets of Marxism can be found in A Contribution to the Critique of the Political Economy originally published in 1859. Found on page ix of the “Author’s Preface” in my copy, Marx makes the all-important point for the worldview that bears his name that “[t]he mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.”

Those two sentences are the load-bearing walls for dialectical materialism/historical materialism that, and messing up my metaphor, is part of the foundation for Marxism. I’m not going to attempt a full-throated explanation of dialectical materialism, but I do believe it’s important for it to frame my next assertion: Marx was influenced by Hegel.[5]

To help, I hope, here’s an oversimplification: Hegel believed that history was moving forward in stages to the final reunion with Geist. The takeaway, I hope, is not “what is Geist?” but that history is marching forward, gradually improving until the final stage – the eschatological stage. This sits at the center of classical liberalism’s belief in (their version of) progress. You can hear it in statements like the arc of history bends toward justice or in the Fukuyamian “end of history” claims on the heels of the Soviet Union’s collapse. It also, albeit filtered through dialectical materialism, is centered in Marxism. Propelled by material changes, Marxism says that history, moving through deterministic stages, will conclude with communism as its eschatological end. Communism is the Marxist heaven, if you will, that is socioeconomically classless, cashless, and stateless (anarchy). Possibly the best example of communism I can think of is Star Trek.

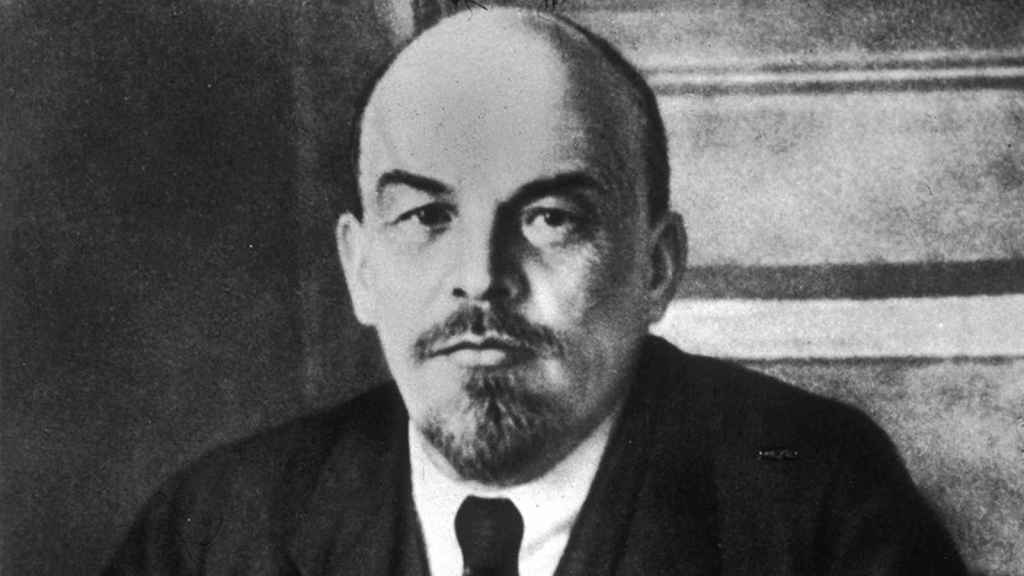

The thing is, according to Marx, capitalism and its inevitable clash between the bourgeois and the proletariat is a necessary, deterministic step in history’s progress. And this is where Lenin (and Trotsky) messed up (messed up if you’re a Marxist – definitely if you’re a fundamentalist Marxist[6]). You see, Russia in the early 20th century had yet to reach the all-important industrialist/capitalist stage necessary in history’s march towards communism. But humans being selfish humans with a deep desire for self-preservation, Lenin realized that attempting a “proletariat revolution” in England or Germany, even if eventually successful, would’ve ensured that he missed out in getting to step into the Promised Land. So, eschewing the role of Marxism’s Moses peering into the Promised Land from the top of a mountain after leading the people to the border, Lenin took the revolution into the still largely agrarian and still kinda-but-not-really feudalistic Russia[7]. Not to mention the “national character” of the Russian peasants who, by and large, loved hierarchies and were decidedly not in the proper stage of Marxist evolution.[8] In other words, Russia, according to Marxism, was the wrong place, wrong time for the revolution. But it made for an easier path for Lenin if you’re willing to ignore, and obviously he was, that a revolution in Russia at the time wasn’t/couldn’t be an actual Marxist one. This helps explain, especially if you are Marxist, why the Soviet Union never achieved communism. Lenin tried to force Marxist eschatology.[9]

You can now probably see where I’m going with my claim that Christian nationalism and Lenin have something in common.

While Jesus often spoke in parables so that some people wouldn’t understand his point (Matthew 13:13), he was unambiguous about what those who follow him should expect in this life. Jesus clearly and repeatedly told his disciples that anyone who picks up his or her cross and follows him should expect to be hated and persecuted.[10] The experience of Christians this side of the eschaton does not include expectations of material comfort, prestige, and power. Those things, if experienced by Christians, are the anomaly not the rule. Until Jesus comes back, his followers, by and large, will be societal pariahs.[11] Christian nationalists, including the Neocalvinists at The Gospel Coalition, believe that Christians can skip all that being persecuted and hated stuff that Jesus went on about and create what amounts to the eschaton in the here and now. This Christian nationalist objective/belief has often been described using John Winthrop’s metaphor of a shining city on a hill. Sadly, though, and using a different metaphor, for Christian nationalists the United States of America is the pot of porridge they’ve traded their eschatological birthright for.

Whether it be the hard-core dominionism of the likes of Douglas Wilson and Stephen Wolfe or the soft “exercising dominion and redeeming culture” via common grace in the appropriate spheres of the Neocalvinist crowd, Christian nationalism amounts to an attempt to override the very clear teaching of Jesus by forcing the eschatology. Just like Lenin.[12]

[1] Technically, I guess, I bought it. The price of the book was added to my school bill. I still have the book, though, if anyone from Mack Library is reading this and wants me to return it almost 30 years later. If that’s the case, I must warn you: I ripped out the BJU disclaimer sticker from inside the front cover. You’ll have to replace it with a new one making sure that anyone who checks it out will know that BJU does not endorse nor agree with everything that Betrand Russell wrote in Roads to Freedom. I mean, it would be a catastrophe if an unsuspecting undergrad checked it out and then began advocating for things like universal health care all because I foolishly removed the disclaimer. So, if you want it back, you can have it. Just promise me you’ll put a new disclaimer in it.

[2] I told very few people this. I mean, I was still a dorm student at BJU, and my self-preservation required select honesty and/or bravery.

[3] I would only make a marginally better Taoist now because my knowledge of Taoism is, well, only marginally better than those few brief months in the mid-90s when I quietly trumpeted my Taoism. And most of what I know of Taoism comes from reading biographies of Genghis Khan.

[4] Marxism is already a fairly dense concept/worldview. I argue that the conflation of terms makes it easier for bad actors – MAGA leaders and MAGA media – to use strawmanning and flat-out deceit to control people. Simply slapping the pejorative tag “communist” on whatever threatens their hegemony makes for a convenient scare tactic; frightened people are much easier to control.

[5] As are you, Mr. Classical Liberal and Mr. MAGA.

[6] All this gets tricky when you factor in Gramsci’s Neomarxism, the stuff, especially by Althusser, coming out of France in the 60s/70s, Italian autonomist Marxism of the 70s, the Post-Marxism of Ernesto Leclau, blah blah, blah.

[7] Serfdom has only been abolished in Russian in1861 and the effects of Alexander II’s reforms were still working themselves out in the early 20th century.

[8] That’s a bad Boasian anthropology, I know. But that doesn’t mean it’s also not true in a helpful general sense. I believe my point stands.

[9] I think I should probably point out that I’m not aware of any Marxist using the term eschatology to describe any part of Marxism. For my purposes, it makes for a handy intuition pump for my intended audience.

[10] I cringe whenever discussions about the persecution of Believers comes up in Sunday school or small groups because those discussions inevitably end up conflating persecution with suffering in general. I mean, for Christians in America that conflation has to happen or otherwise Christians in America have to confront themselves with why our experience contradicts what Jesus told us to expect. I can’t count the number of times discussions about the persecution of Christians includes talking about how someone has cancer or someone lost their job. I mean, unless you lost your job because you’re a Christian (or got cancer because you’re a Christian, which doesn’t even make any sense), that ain’t persecution and it’s disrespectful to Christians who have been and are being persecuted for Christ’s sake to conflate the two.

[11] This raises a question that I frequently ask but have yet to get an answer from pastors, theologians, etc. that if Christians, by and large, are not societal pariahs in America, and, by and large, they’re not, doesn’t that call into question the validity of what’s called Christianity in America? I mean, either Jesus was wrong or Christianity in America is not Christianity … there, I said it out loud.

[12] Another commonality between Christian nationalism and Lenin is the necessity to not just punish but to squash dissent. If Christian nationalists are able to turn the USA into their form of a theocracy, then like all totalitarian states persecution will soon follow.

John, have you read C.S. Lewis’ Studies on Words? You are certainly not the only one troubled by conflation of meanings. Clear communication is harder than it seems. Forcing someone to use words exactly as you use them may be pedantic, but wanting clear definitions is certainly not. Rather, it’s essential for common ground in dialogue.

LikeLiked by 1 person