by John Ellis

During my junior year of high school, Christian fundamentalist Michael Griffin shot and killed Dr. David Gunn. What makes this noteworthy, besides the murder taking place in my hometown of Pensacola, FL, is that Dr. Gunn was an abortion doctor and Griffin an anti-abortion extremist. A little over a year later, on July 29, 1994, Dr. John Bayard Britton, Dr. Gunn’s replacement, was murdered by Paul Jennings Hill. Correctly assuming that Dr. Britton was wearing a bullet proof vest, Hill shot him in the head with a twelve-gauge shotgun and then turned the gun on Britton’s bodyguard, James Herman Barrett, Jr., killing him, too. The abortion clinic where Dr. Britton was murdered had been fire-bombed twice in 1984 and then again in 2012.

While I remember the assassination of Dr. Gunn, I don’t remember the clinic bombings in 1984. The aftermath of Dr. Britton’s assassination, though, stands out vividly to me. That summer, before heading off to Bob Jones University for my freshman year, I worked at Merchant’s Paper Company. My primary job was loading and unloading trucks and keeping the warehouse clean and organized. Whenever one of the regular drivers called in sick, I was tasked with delivering office and restaurant supplies. During one of the days that found me escaping the monotony of the warehouse, I unwittingly turned the white van onto a downtown Pensacola street occupied by anti-abortion protesters. While making a three-point turn to find a different route, angry protesters screamed at me while banging on the sides of the van. More confused in the moment than scared, I was puzzled as to why anti-abortion protesters were mad at me. I have since learned that ideologically driven anger is often unfocused and uncontrolled. I just happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time. The experience also gave me a firsthand look at how anger and political violence are inevitable when a tug-of-war over the nation’s direction is happening.

Over the last month, as people have asked my thoughts about the assassination of Charlie Kirk, as well as reading multiple op-eds and social media posts about the tragedy,[1] I’ve thought back to the political violence that roiled my hometown while I was growing up. I’ve also thought about all of it – Charlie Kirk’s assassination and the responses to it – within the broader context of United States history. In doing so, two important points have established themselves in my mind:

1. No one should be surprised. Political violence is part of this country’s DNA. 2. The American experiment is proving unworkable. The societal divisions – cultural wars – are unbridgeable and, therefore, unresolvable, making the continuation of the Republic (as is) unsustainable.

(Those two points are going to be discussed in separate articles.)

Political Violence Is Part of this Country’s DNA

After Parliament approved the Stamp Act in 1765,[2] the English colonies in America angrily erupted in violence. Upon its enaction, “The response was immediate and full-throated in its militance.”[3] As colonial legislatures debated responses, the anger of the colonists boiled over towards the end of the summer. The riots began in Boston, quickly spreading throughout the other colonies. Destruction of property, including the houses of Parliament’s stamp agents, was a primary means by which the rioters voiced their displeasure. The newly organized Sons of Liberty, the combination of two Boston gangs whose violent tendencies had been harnessed together by Dr. Thomas Young,[4] had their riotous energies deliberately turned towards the Stamp Act and those entrusted with enforcing it. During the weeks of rioting, “the house of Thomas Hutchinson, the Lieutenant-Governor of Massachusetts, was looted and burned so badly that the next morning only its frame was still standing. … The mob intended to ‘tar and feather’ Hutchinson, but he at least escaped that brutal, twelfth-century European punishment of pain and humiliation.”[5] The rioters made it clear, “Parliament would not be able to legislate its authority in America without coercion.”[6]

Regardless of one’s beliefs about the (British) constitutional validity of the Stamp Act, the die had been cast: political violence was firmly entrenched as a primary means of political expression among the colonists.[7] Political violence by the people begets coercive responses from the authorities (and vice versa), often culminating in even more violence. And this cycle of violence carried over into the young Republic, even after the believed yoke of oppression at the hands of Parliament and King George III had been thrown off. It was quickly revealed after the Treaty of Paris that the revolt against England had papered over very real divides among the colonists.[8] As Gary Nash argues, the Revolution was “an upheaval among the most heterogeneous people to be found anywhere along the Atlantic littoral in the eighteenth century.”[9] Without a common enemy, those divides threatened to destroy the United States of America right out of the gate. Two examples, out of a possible many, will suffice.

It’s impossible, I believe, to truly understand the history of the United States of America without coming to terms with the Whiskey Rebellion.[10] The brewing, natural antagonism between the hierarchical federalists – George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, et al. – and the democratically inclined among the people, especially those in the western reaches of the new nation, is as important to the story of this country as are the more widely known events used as answers in multiple choice quizzes in history classes covering the founding of this country. In some cases, the Whiskey Rebellion is even more important to that story. It challenges the collective mythology of homogeneity about this country’s early years. I encourage readers to study the Whiskey Rebellion for themselves.[11] For this article’s purpose, what’s important is that the class/political antagonism posed a serious existential threat to this country from the start. So much so, that George Washington remains the only president to lead troops into battle while president. That battle didn’t happen, though. George Washington’s imposing presence, as much as the show of force, squelched the spreading rebellion, but not before the Western rebels had engaged in quite a bit of violent terrorizing of government agents and officials.

Referring to it as the Whiskey Insurrection, historians Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick provide an expansive picture by pointing out that, “In view of the numbers involved, and inasmuch as the entire region appeared on the verge of armed rebellion by midsummer, one can only conclude that this feeling [of widespread hostility to the federal excise on whiskey] had struck deep in every community, and may thus be regarded as an authentic popular manifestation.”[12] Before Washington suppressed this “authentic popular manifestation,” violence rocked the region.

It didn’t help matters that Hamilton appointed General John Neville to oversee the collection of the whiskey tax. You see, “General Neville was also a large-scale [whiskey] distiller. The leading local beneficiary of the tax had been given the job of enforcing and collecting it.”[13] That political misstep exacerbated events that were already leading to tragic consequences.[14]

To register the whiskey stills and serve warrants for non-compliance, “General Neville’s first hire was Robert Johnson – waylaid, tortured, and humiliated.”[15] John Fox, a deputy federal marshal, was commissioned to arrest Johnson’s attackers. Fox, however, realizing that the locals were after blood, specifically the blood of federal agents, begged off the job. Inscrutably, General Neville recommended that Fox hire a local cattle drover named John Connor to do his job for him. William Hogeland describes Connor as “ancient” and then details the gruesome fate of the elderly man. “[Connor] encountered a gang that took him into the woods and began by using a horsewhip on him. His naked body, stripes new and raw, received the blistering tar. He was stuck with feathers, tied up, and left in the woods in agony, his horse, money, and warrants seized.”[16]

The event that finally prompted the Washington administration to wake up to the seriousness of the growing revolt was the attack and subsequent ransacking and burning of General Neville’s house and its immediate aftermath. “On July 16, 1794, about five hundred men … converged on Neville’s house at Bower Hill with the object of forcing the Inspector to resign his commission. The place was defended by Nevill and members of his household, assisted by a handful of soldiers from the nearby military post, in the course of which two of the besiegers were killed, including their commander, and six others wounded. After the defenders made their escape, the cellar was looted and the house burned.”[17] After the attack on Neville’s house, a mob numbering close to six thousand descended on Pittsburgh, threatening to destroy it. President Washington decided to intervene, hoping to squash what was obviously the beginning of a civil war.

The Whiskey Rebellion wasn’t the only political turmoil that caused George Washington to regret leaving Mount Vernon for the privilege of becoming the first president.[18] Flinging fuel on the fire of acrimony that was consuming Washington’s cabinet,[19] the Jay Treaty and its aftermath may have been the final straw that convinced the President to not seek a third term. It was definitely what finally ended the friendship between James Madison and George Washington. And it was also accompanied by political violence.

In Empire of Liberty, Gordon S. Wood writes, “When the terms of the [Jay] treaty were prematurely leaked to the press, the country went wild. [John] Jay was burned in effigy … [Alexander] Hamilton was stoned in New York when he tried to speak in favor of the treaty.”[20] A few pages later, the noted historian argues that “[e]xcept for the era of the Civil War, the last several years of the eighteenth century were the most politically contentious in United States history.”[21] Empire of Liberty was published in 2009, over a decade prior to the attempted insurrection on January 6, 2021, and the subsequent disintegration of political and cultural discourse and the accompanying violence.

I’m not sure where Dr. Wood rates today’s political contention on the historical scale. His pointing to the Civil War is important, though. I believe that the decade leading up to it provides a prophetic parallel for today. There is a through-line-of-action running from 1765 through the burgeoning republic and all the way to the present time and the assassination of Charlie Kirk. It’s a through-line-of-action that reveals continuous divisions in this country.[22] The United States of America has never been as united as advertised. Different understandings of what this country is and competing visions of what it should/can be have always existed in American culture. In certain eras, though, those divisions are revealed to be wider than generally assumed. And the 1850s have a lot to tell us about what happens when the divide becomes too wide.

The mood and state of the country leading up to the Civil War was summarized by Abraham Lincoln on June 17, 1858, when he warned that a house divided against itself cannot stand.[23] After quoting Mark 3:25, the Senate hopeful added, “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I do not expect the house to fall; but I do expect it will cease to be divided. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new, North as well as South.”[24]

By the mid-point of 1858, and a mere two years before being elected to the White House, Abraham Lincoln surveyed a country – a house – coming apart at the seams. He realized that the country either had to become all slave or all free. He was wrong, of course, about the dissolution of the Union; it did dissolve, if only temporarily. Granted, a politician seeking office would be ill-advised to prophesy an imminent, unavoidable (at that point) Civil War. Based on his future actions, though, it’s safe to assume that Lincoln understood not only the gravity of the problem but that the nation was barreling to dissolution. There are reasons why historians almost unanimously rate Lincoln as this country’s greatest president. It’s hard to envision any other person saving the Union. In 1858, Lincoln looked at the signs and realized that the divide between slave and free states was too wide to be bridged; common ground, and even agreeing to disagree, was not possible. The secession of the Southern states began even before Lincoln had been inaugurated. They knew what his election meant: the death knell to their program to “push [slavery] forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new, North as well as South.”

A little over a year prior to Lincoln’s “House Divided” speech, Chief Justice Roger Taney had issued his infamous decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford,[25] stripping Black people – all Black people – of their United States citizenship.[26] Beyond stripping Black people of their citizenship, Taney’s Dred Scott decision sealed the nullification of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Furthermore, according to many historians and constitutional scholars, Taney’s decision also overturned Douglas’ prized principle of popular sovereignty. “The Richmond Enquirer insisted that Dred Scott had affirmed the southern position that the territories were ‘the common domain of all the United States, and, as such, the people of each and every state have an irrefutable right to transfer themselves and their property into it.’”[27] All territories were open to slavery, regardless of what their populations desired, according to the Supreme Court.

The doorway to Taney’s decision had been opened in 1847 when the enslaved Dred Scott had sued for his freedom. Since his previous enslaver had moved him to the Wisconsin territory and later to the State of Illinois, slavery being prohibited in both, Scott claimed that he had been emancipated. Ruling against Scott, with Taney’s decision “[t]he Court had declared slavery to be a national institution that Congress could not prohibit in the territories.”[28] Opening the door to the spread of slavery throughout the entire nation, Taney swatted aside the irksome fact that Scott had lived for two years in Illinois, a free state, declaring, “As Scott was a slave when taken into the State of Illinois by his owner, and was held there as such … his status, as free or slave, depended on the laws of Missouri, and not of Illinois.”[29]

If an enslaver could take an enslaved person into a free state for two years and the status of the enslaved person not be changed, why not three years? Or four? Or ten? Or why not for as long as the enslaver wants? The various sojourner laws in the Northern states were, for all intents and purpose, declared unconstitutional. Abraham Lincoln was one who understood this ramification of the Dred Scott decision.

During his “House Divided” speech, a speech directly responding to the decision, the future President made the salient point that “the logical conclusion that what Dred Scott’s master might lawfully do with Dred Scott, in the free State of Illinois, every other master may lawfully do with any other one, or the one thousand slaves, in Illinois, or in any other free State.”[30]

For decades prior, Southern states had complained that Northern sojourner laws were unconstitutional.[31] With Dred Scott, the Supreme Court ruled they were correct. A second“Dred Scott” decision was all that was needed to ostensibly extend slavery throughout the entire nation. And another potential “Dred Scott” decision was already making its way through the courts.

Initially decided against the enslavers in 1852, with Lemmon v. The People the State of New York had “freed a number of slaves that were merely in transit from Virgina to Texas by coastal vessel.”[32] But it was making its way through the appellate courts. After the1857 Dred Scott decision, Lemmon v. The People was the case “that many Republicans feared would provide the Taney court with an opening wedge”[33] to expand slavery across the entire nation. It would have provided Taney the opportunity to declare that enslavers’ property – enslaved people – was Constitutionally protected in every square inch of the Republic. That would have permitted enslavers from the South to move with their property, including enslaved people, to the North and become citizens of free states without fear of being forced by sojourner laws to manumit their slaves. In case that wasn’t clear, a free state would become a slave state as soon as an enslaver decided to move there. The Civil War erupted before Lemon could make it onto the Supreme Court’s docket, though.

As the decade came to a close, the Slave Powers were watching their well-laid plans come to fruition. The Dred Scott decision was an important domino to fall after the Kansas-Nebraska Act.

In 1854, the reigning “king” of Doughfaces,[34] Senator Douglas was used by the four senators – David Rice Atchison (MO), Andrew Pickens Butler (SC), Robert M.T. Hunter (VA), and James Murray Mason (VA) – known as the F Street Mess to forward the cause of the Slave Powers.[35] Focused on getting a transcontinental railroad approved by Congress, specifically a central route that would establish depots in both Chicago and St. Louis, two areas where Douglas had significant real estate holdings,[36] Douglas opened himself up to being used as a puppet by the politically savvy F Street Mess. He desperately wanted an appointment to the Committee on the Pacific Railroad, an appointment determined by the Senate president pro tempore, a seat filled during the 33rd Congress by David Rice Atchison.

Douglas’ initial bill, introduced on January 4, 1854, did not mention the Missouri Compromise. An attached report did, however. Attempting to appease all sides, he argued in the report for the principle of popular sovereignty in deciding slavery questions in future territories. The January 4 version of the bill and attached report is believed to be Douglas’ attempt “to avoid outright repeal of the Missouri Compromise and still appease Atchison.”[37] It didn’t work.

On January 10, the Washington Sentinel published the text of a reworked Nebraska Senate Bill. The new version of the bill included a section nullifying the Missouri Compromise and opening slavery to all new territories and states in the Union. Dr. Malavasic argues that “physical and circumstantial evidence supports the argument that Douglas was forced by the F Street Mess to add the section.”[38] It should be noted that on January 9, Atchison announced the appointment of Douglas to the Committee on the Pacific Railroad. Led by the F Street Mess, the Slave Powers manipulated the levers of power to ensure slavery’s survival via aiding its spread into new territories.[39] Commenting on the Northern response to his Kansas-Nebraska Act, Stephen Douglas joked, “I could travel from Boston to Chicago by the light of my own effigy.”[40]

Four years later, as already noted, the Slave Powers saw their agenda advanced even further by the Supreme Court. The Dred Scott decision appeared to overrule the principle of popular sovereignty by codifying the right of enslavers to take (and keep) their slaves wherever they wanted as well as claiming that neither Congress nor Territory legislatures could ban slavery in any US territory.

Slavery, specifically the Slave Powers’ machinations to extend slavery throughout the entire country, was the political backdrop for the violence of the 1850s. Northerners, even those who weren’t abolitionists, began to open their eyes to the inevitable consequences of the Slave Powers’ actions. The country was headed towards a future that enshrined slavery throughout the entire nation. For their part, the Slave Powers understood that unless slavery became the law of the entire land, their rights to enslave Black people would eventually be taken away. A house divided against itself cannot stand. Slavery was the central seam upon which the nation was being ripped apart.[41] Before the final conflagration, political violence erupted in this country at levels not seen since the end of the previous century.

Things started to boil over during Congressional debates over the Compromise of 1850, revealing that the Jacksonian Age was officially over.[42] The country had transitioned from the so-called Second Party System to a nation characterized by sectional division. One of the sticking points was the admission of California as a free state. The Southern states were worried that their outsized influence on national politics, thanks to the 3/5ths compromise in the Constitution and the electoral college, was in serious jeopardy.[43]

Led by Mississippi Senator Henry Foote, the Southern states pushed for pro-slavery measures, like a beefed-up Fugitive Slave Act, to be included in the compromise. If Congress failed to acquiesce to their demands, secession was threatened. President Zachory Taylor vowed to use military force if any Southern states dared attempt taking steps towards secession. “Some observers worried however, that the violence that would begin disunion might erupt in Congress itself. … Several reporters remarked at the frequency with which congressmen carried concealed pistols in the Senate and House. … One rumor circulated that a general melee was to be staged in Congress, coordinated with plans to blow up the Capitol and White House.” Historian Mark Stegmaier concluded, “Given the guns and knives in abundance, such rumors should have surprised no one.”[44]

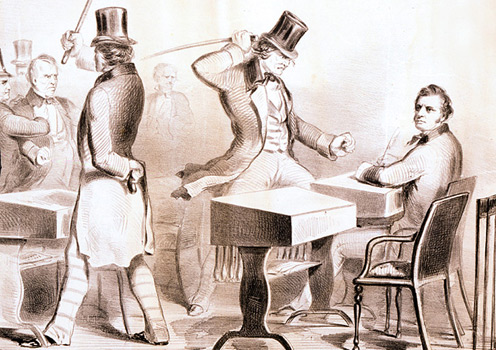

Violence almost catastrophically erupted on April 17, 1850. Angry at Senator Foote’s insulting denunciation of him during a floor speech, Senator Thomas Hart Benton (MO) charged Foote. Other Senators intervened, stopping Benton and convincing him to return to his seat. That’s “when Benton suddenly noticed that Foote had pulled a loaded, five-chambered revolver from his pocket. Benton again advanced down an aisle toward Foote, asking all to take notice that Foote had brought a gun there to assassinate him with.”[45] The escalating altercation was halted after several Senators physically restrained Benton and Foote surrendered his revolver. Six years later, on that very same Senate floor, Congressman Preston Brooks (SC) nearly beat Senator Charles Sumner (MA) to death with a cane. Brooks was angered by an anti-slavery speech Senator Sumner had delivered; a speech in which Sumner had criticized Senator Andrew Butler (SC), Brooks’ cousin.[46]

While mostly reduced to interesting trivia questions now, those two events were not culturally anomalous. Both reflect the hot anger that characterized the divide over slavery in this country. For example, the caning of Sumner in 1856 was one event connected to what is known as the Bleeding Kansas Crisis. In fact, it was the event that finally prompted John Brown to begin his murderous rampage against slavery. John Brown wasn’t the only one, though. The political violence of the 1850s found a convenient home in the territory of Kansas. The State of Kansas’ history website estimates “that at least 60 and possibly as many 200 people died for political reasons” in the territory during the period. Direct violence, including murder, wasn’t the only form of political violence to unsettle the territory.

“Popular sovereignty intimately bound migration to politics in a way unprecedented for the United States. Through the ballot box, Kansas settlers were to decide the contested issue of slavery.”[47] But Stephen Douglas’ popular sovereignty was waylaid and hijacked by enslavers desperate to extend slavery into the territory. The pro-slavery secret society “the Blue Lodges promised Missourians who would vote in Kansas ‘free ferry, a dollar a day, & liquor.’”[48] Spread across the state of Missouri, the secret society terrorized abolitionists in the state. With local law on their side, abolitionists were arrested, beaten, and then forced to leave the state after being forbidden from entering Kansas. The violence and abuse of the legal system by those wanting to extend slavery into the new territory of Kansas parallels a growing body of laws in the South during the first half of the 19th century aimed at Northern abolitionists.

As the 19th century progressed, abolitionists solidified their message around the immorality of slavery. Gradual abolition was deemed anathema, and a full-throated attack on the great sin of the nation began in earnest. “Abolitionists prosecuted slavery mercilessly, giving the lie to the paternalistic protests of masters who claimed they loved their slaves and their slaves loved them. This was an aggressive rhetoric that abandoned politeness. It was a democratic rhetoric, too.”[49]

This escalating rhetoric, damning enslavers as unrighteous and enemies of the country, frightened offended Southerners already on edge after the attempted slave insurrections of Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner. Claiming that abolitionists were encouraging enslaved people to rise up and murder them, Southerners fought back.

Southern legislatures acted quickly to suppress the growing abolitionist literature flowing from the North. Much of the Southern ire was directed at arch-abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. North Carolina indicted him for distributing incendiary material. In South Carolina, a $1,500 reward was offered for the arrest and conviction of any white person caught distributing Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. “In Georgia the legislature upped the ante by offering a reward of $5,000 for anyone who arrested Garrison and brought him to the state to be tried for seditious libel.”[50]

As early as “February 1836, five southern legislatures had passed resolutions essentially demanding that the northern states restrict abolitionist speech.”[51] H. Baker also tells us that, “In Georgetown, a mob hunting for a mulatto (said to have spoken ill of a white man’s wife and daughter) found abolitionist papers in the home of the man thought to be harboring him. The homeowner was committed to jail, but likely for his own protection, as the mob ransacked his house.”[52] However, all this, and the scores of other violent incidents, divisive rhetoric, and acts of Southern legislatures directed at abolitionists, was merely a prologue to the violence that accompanied Kansas’ Lecompton Constitution.

On December 21, 1857, via a rigged election, the Lecompton Constitution codified slavery in Kansas while prohibiting free Blacks from settling in the territory/future state. Just a couple of weeks later, on January 4, a “free-state referendum on Lecompton resoundingly defeated the constitution.”[53] A majority of voters in Kansas had rejected the pro-slavery constitution. This didn’t stop President Buchanan from sending the Lecompton Constitution to Congress with instructions to admit Kansas as a state under it. This divided the national Democrat Party, with former Southern allies, most notably Stephen Douglas, refusing to support a constitution rejected by the majority of Kansas voters.

Just after 2 a.m. on February 6, 1858, during debates over Kansas statehood, a fight broke out on the floor of the House of Representatives. The fight started when Democrat Congressman Laurence Keitt (SC) attacked Republican Congressman Galusha Grow (PA). “Other congressmen joined in until it became difficult to distinguish the combatants from those trying to restrain them.”[54] The shameful fight on the House Floor is almost comical, though, compared to the very real violence enacted in Kansas and across the nation during the years surrounding the Lecompton Constitution. The debates over whether Kansas would be slave or free seemed to many to be a referendum on the direction of the country. And it wasn’t just the proslavery side that committed acts of violence. “[John] Brown, along with his sons and followers, committed violent deeds unprecedented in the history of American antislavery activism.”[55]

“The Richmond Enquirer, the South’s leading paper,” speaking for the South and enslavers at large, “called antislavery senators ‘a pack of curs’ who ‘have become saucy, and dare to be impudent to gentleman’ and thus ‘must be lashed into submission. … Let them once understand, that for every vile word spoken against the South, they will suffer so many stripes, and they will soon learn to behave themselves like decent dogs – they can never be gentleman.’”[56]

The nation was splitting at the seams, coming apart over differing visions of America. In a long, instructive quote from her book Bleeding Kansas, historian Nicole Etcheson puts it well when she writes, “From the concrete historical event of the Revolution, Americans constructed their national identity. A reverence for that founding moment remained powerful for people of both the North and the South. Ironically, Bleeding Kansas made it clear that Northerners and Southerners had drawn very different conclusions about the meaning of that historical event, and thus about the nature of U.S. nationalism. If a nation is indeed ‘an imagined community’ in which people who do not know each other nonetheless believe they share a commonality, then North and South had imagined different communities based on Revolutionary principles. The conflict in Kansas served to make painfully clear the differences in those communities.”[57]

One of the challenges I faced writing this article was deciding which acts of violence, either in word or deed, to include. I then had to pare down that list. I tried to pick examples that spoke clearly to the divisions while highlighting the extremes that people on both sides of the debate were willing to go to advance their vision of America. Even now, I’m second guessing my choices, but am aware that’s more from my desire to tell the entire history of this country in one article, which is an unhelpful impulse I’m sure, than from any real belief that other examples would better prove my point. And my main point in part one is this: The United States of America has always been divided, and those divisions have frequently devolved into violence. The 1850s cry to us from the past about the extremely bloody endgame their divisions terminated in – the Civil War.

Should we mourn that Charlie Kirk and Melissa and Mark Hortman tragically lost their lives at the hands of political violence this past summer? Of course. Should we feel angry that the families of Kirk and the Hortmans had their loved ones ripped away too soon? Absolutely. But should we be surprised? And this article is my attempt to resoundingly answer, “no.”

Surprise over political violence is unhelpful because it’s ahistorical and obscures our ability to recognize hard truths about our society. And the truth is that the house is divided. It’s not quarrelling; it’s not a family spat; it’s two, at the least, separate houses, just like in the 1850s. Mirroring its own history, the United States of America in 2025 is not one nation, which is the topic of Part Two.

[1] I’m not on social media. My wife showed me some posts from people I know, members of our church, etc., reminding me of why I’m not on social media.

[2] I could’ve gone further back in time, Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676-77 being a prime example. I picked 1765 because that as good as a flash point as any to begin pointing to the coalescing of the colonists as some sort of entity/group working towards the common goal of independence instead of 13 disparate and separate political organizations. The problem, as I’ll show, is that the divisions between the colonies (and within colonies) carried into the unified political organization that declared its independence from England. Those divisions quickly created problems.

[3] Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 138.

[4] William Hogeland, Declaration: The Nine Tumultuous Weeks When America Became Independent, May 1 – July 4, 1776 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 18.

[5] Andrew Roberts, The Last King of America: The Misunderstood Reign of George III (New York: Penguin Books, 2023), 158-159.

[6] Francis D. Cogliano, Revolutionary America, 1763-1815: A Political History 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2009), 58.

[7] To be fair, this wasn’t unique to the colonists. Political violence has been part and parcel of the history of the West, at least.

[8] To get a better picture of this, I encourage readers to look into what happened in Pennsylvania leading up to July 1776. Samuel Adams and his cousin John Adams, along with other prominent future federalists, allied with advocates of popular democracy – Thomas Young, Benjamin Rush, Thomas Paine, James Cannon, et al. – to “overthrow” the PA statehouse, undercutting John Dickinson’s refusal to allow the PA delegation to the Second Continental Congress to vote for independence from England. The Adams cousins helped create a democratic state government and constitution in PA that they would never have allowed in MA to achieve their goal of removing themselves out from under the mercantilist priorities of England.

[9] Gary Nash, The Unknown American Revolution: The Unruly Birth of Democracy and the Struggle to Create America (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), xv.

[10] I also believe this to be true about Shay’s Rebellion. A compelling – almost airtight – argument can be (and has been) made that without the shock of Shay’s Rebellion and the fear it generated, especially on George Washington, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 would not have happened.

[11] I recommend starting with The Whiskey Rebellion by William Hogeland.

[12] Stanley Elkins and Eric McKitrick, The Age of Federalism: The Early American Republic, 1788-1800 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 461-462.

[13] William Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Halmiton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America’s Newfound Sovereignty (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006), 97.

[14] I’m not sure if “misstep” is the right word. A. Hamilton believed so firmly in class hierarchism and in the correctness of his actions in using economics to shape the new country that I suspect he lacked the ability to empathize with struggling farmers’ anger at having General Neville serve both as a beneficiary of the tax and the one enforcing it. In his mind, everyone was supposed to play their part. And the peoples’ part was supposed to be one of trust and deference to their social betters/leaders.

[15] Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion, 103.

[16] Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion, 103-104.

[17] Elkins and McKitrick, The Age of Federalism, 463.

[18] Much is made of George Washington willfully laying aside power, and for good reasons, to be clear. However, he never wanted to leave Mount Vernon and return to public service and was embarrassed to do so since he had sworn to retire to private life after surrendering his sword to Congress after the Revolution. Being the first president of a struggling, bankrupt, “barely” nation in place of overseeing his beloved plantation while ensuring the growth of his personal wealth isn’t the glamorous job often pretended. He hated being president and couldn’t wait to leave the office behind him.

[19] On February 25, 1791, President Washington, against their strong advice, signed the bill chartering the Bank of the United States. This was the first real alarm bell warning Jefferson and Madison (but especially Madison) that Washington may not be whom they believed him to be.

[20] Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 198.

[21] Wood, Empire of Liberty, 209.

[22] The divisions aren’t always the same, to be clear.

[23] Elbridge Gerry (of gerrymandering fame) used the Biblical metaphor in 1810 to warn about partisan divisions.

[24] “Lincoln’s House Divided Speech” Documents of American History ed. Henry Steele Commager (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1963), 345.

[25] An interesting historical note: it was actually Sanford, but it was recorded incorrectly and has gone down in history as Sandford.

[26] The decision was originally supposed to be released in 1856, but James Buchanan was afraid it would influence the upcoming election, thwarting his desire to become President. His good buddy Roger Taney agreed to sit on the decision until right after Buchanan was inaugurated, protecting his election chances and saving the President-elect from having to confront the subsequent firestorm before even assuming office. There is also evidence that Buchanan colluded with Taney on the wording of the decision – a blatant violation of the Constitutionally mandated separation of powers.

[27] Nicole Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty In the Civil War Era (Lawrence, KA: University Press of Kansas, 2004), 143.

[28] Tony Mauro, The Supreme Court Landmark Decisions: 20 Cases that Changed America (New York: Fall River Press, 2016), 17.

[29] Cited by Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1978), 385.

[30] “Lincoln’s House Divided Speech” Documents of American History, 347.

[31] I’m not sure, yet, if I’ll explore this more in the next two “Charlie Kirk” articles, but the sojourner cases during the 19th century have contemporary parallels in the various state abortion laws in the wake of SCOTUS overturning Roe. Considering the makeup of the Court, I know what will happen, but it will still be interesting, from a historical perspective, to see the result of a case when an anti-abortion state takes a pro-abortion state to court for refusing to extradite a doctor for providing an abortion to an citizen of the anti-abortion state, or for sending abortifacients through the mail.

[32] Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case, 60-61.

[33] Leonard L. Richards, The Slave Power: The Free North and Southern Domination, 1780-1860 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2000), 15.

[34] Doughface was the pejorative assigned to Northern politicians who served the interests of the South.

[35] The four Southern Senators roomed – messed – together in a house on F Street.

[36] He had made these real estate purchases, and others, with the expectation the rail line to immensely increase his wealth. It’s not that he already owned the land and then saw an opportunity, which would also be unethical. He deliberately used his position of power to increase his wealth.

[37] Alice Elizabeth Malavasic, The F Street Mess: How Southern Senators Rewrote the Kansas-Nebraska Act (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 89.

[38] Malavasic, The F Street Mess, 90.

[39] After the publication of the rewritten bill on Jan. 10, Democrat congressman Philip Phillips (AL), who was a legal scholar, argued successfully to F Street Mess member Senator Robert Hunter that the bill, specifically section 21, didn’t actually overturn the MO Compromise. The hated, by the Slave Powers, compromise would still be in effect. On Jan. 16, Senator Archibold Dixon (KY) introduced an amendment that explicitly repealed the MO Compromise. After some further political intrigue, including a back room deal with President Franklin Pierce, the Douglas Nebraska Bill without the Dixon amendment was signed into law on May 30, 1854, by President Pierce. The final bill included a rewritten section 14 that “superseded” the MO Compromise and codified the principle of popular sovereignty in deciding the slavery question.

[40] Quoted by Roy Morris, Jr., The Long Pursuit: Abraham Lincoln’s Thirty-Year Struggle with Stephen Douglas for the Heart and Soul of America (New York: Harper Collins, 2008), 73.

[41] For those who continue to insist that the slavery wasn’t the main cause of the Civil War, you have to answer, among other questions, why the Southern states turned their backs on Stephen Douglas in 1860.

[42] The Jacksonian Age wasn’t minus its own serious squabbles, to be clear. I mean, the Nullification Crisis was a big one.

[43] That influence had already been steadily chipped away at as the population boomed in the free states, especially in those states in what had been originally called the Northwest Territory – Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin had all achieved statehood by 1848.

[44] Mark Stegmaier, Texas, New Mexico and the Compromise of 1850: Boundary Dispute and Sectional Crisis (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2012), 104.

[45] Stegmaier, Texas, New Mexico and the Compromise of 1850, 114.

[46] The Federalist/Antifederalist divide also produced its share of violence in Congress. On Feb. 15, 1798, Congressman Roger Griswold (CT) attacked Congressman Matthew Lyon (VT) with his walking stick. Lyon defended himself with fireplace tongs. The fight had been precipitated by a couple weeks’ worth of angry words and insults between the two, including Griswold calling Lyon a coward and calling into question his military service during the Revolution. At one point, Lyon spit tobacco juice in Griswold’s eye. The Federalists attempted to have him kicked out of Congress but were unable to muster the needed two-thirds majority. An impatient Griswold took matters into his own hands. The quarrel/fight between the two was over President Adam’s preparations for war against France. The Antifederalists/Republicans believed the Federalists were moving the country back to a monarchy.

[47] Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas, 50-51.

[48] Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas, 32.

[49] H. Robert Baker, Prigg V. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution (Lawrence, KA: University Press of Kansas, 2012), 87.

[50] Henry Mayer, All On Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), 122-123.

[51] Baker, Prigg V. Pennsylvania, 115.

[52] Baker, Prigg V. Pennsylvania, 114.

[53] Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas, 163.

[54] Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas, 169.

[55] Davis S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005), 152-153.

[56] Reynolds, John Brown, 161.

[57] Etcheson, Bleeding Kansas, 5.