“If the federal government were to go out of business, the common run of people would not detect the difference.” Calvin Coolidge

By John Ellis

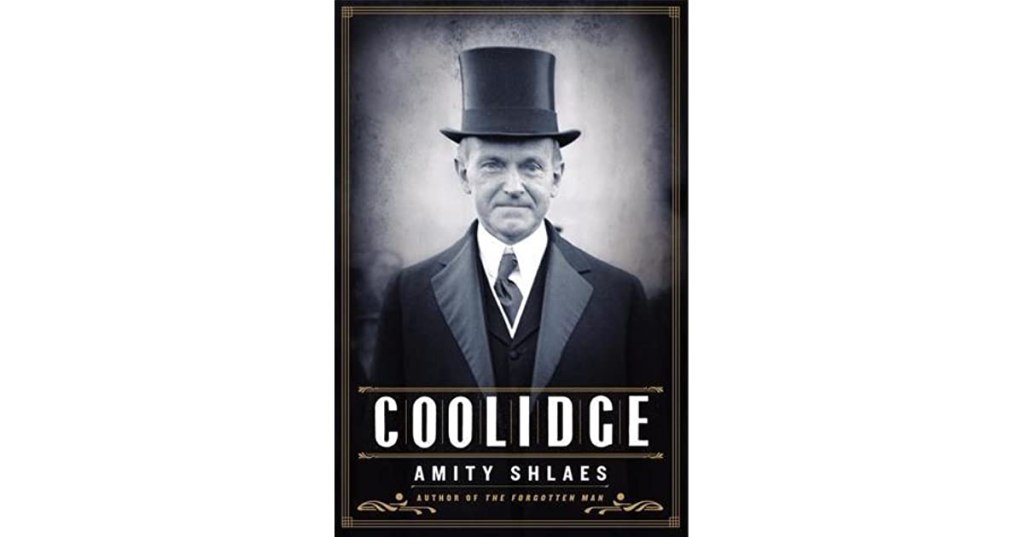

Calvin Coolidge is a hero (maybe the hero) for old-school conservatives who still stubbornly cling to the classical liberalism that was long valued but now scorned by the bulk of the Republican party. Amity Shlaes’engaging biography Coolidge was published prior to 2016, during a time when Republican royalty revered Coolidge and fought to have his memory and accomplishments canonized near the top of presidential best-of lists. Now, though, having sold their souls to Donald Trump and his cynical, self-serving MAGA nationalist ideology, I doubt if once conservative stalwarts like Hillsdale College, the Heritage Foundation, and the RNC are as willing to lobby for Coolidge’s visage to be carved into the side of Mount Rushmore as Sarah Palin once was. On one hand, that’s a shame. For all the flaws and blind spots of the pre-2016 Republican Party, the GOP offered a legitimate alternative to the DNC (which, to be fair, has its own flaws and blind spots)[1] as well as adding thoughtful discourse to the never-ceasing political debate. On the other hand, like most, if not all, of this country’s presidents, Calvin Coolidge does not deserve canonization. If you were to believe Coolidge by Amity Shlaes, though, you might beg to differ.

The book is a well-written and well-researched (to be clear) yet subtle pseudo-hagiography, which makes Shlaes’ biography of the 30th president all the more dangerous; while reading the book, it’s hard to resist wanting to follow in Ronald Reagan’s footsteps who replaced a portrait of Harry Truman with Calvin Coolidge in the Cabinet Room. Shlaes does her job well, and that’s the problem.

While it’s true that Calvin Coolidge can be rightfully held up as a bulwark of classical liberalism between the previously reformed minded Republican presidents like Teddy Roosevelt and Warren Harding and the full-tilt progressivism of FDR and Truman, it’s also equally true that arguments can be made that his policies helped usher in the Great Depression.[2] However, it is not my goal to make those arguments – to dismantle Shlaes’ portrait – nor to tarnish Coolidge’s reputation; the man had many admirable qualities that I wish contemporary Republicans would emulate. His personal virtue and integrity speak to one of my purposes in writing this: a call as well as a warning to thoughtful conservatives. My other purpose is to offer a warning for non-historians (including myself) when reading history books, and this is the objective I’ll tackle first (because it’s the easiest).

Proper Historiography

Recently, a professional historian I follow on Twitter – Thomas LeCaque, an Associate Professor of History at Grand View University – tweeted a thread that helpfully underlines the importance of proper historiography. In the first tweet of the thread, LeCaque observed, “Reading books is great, everyone should read more books, and heck, I’d love it if everyone read more history books, but that doesn’t make you a historian. [It] makes you a reader! Which is a great start!” He then went on to confront self-proclaimed (amateur) historians with questions about their historiography. Questions like, “Do you go back to [the author’s] primary sources to analyze them? Have you looked into [the author’s] personal background to try and figure out their worldview, biases, reasons for writing, political and social and cultural and religious contexts? Have you gone to the archives? Did you get training to deal with primary documents in the field? Have you learned to make complex arguments from the books and primary sources you’ve read? Have you learned to deal with the biased, incomplete, scattered, problematic nature of all historical records, ingrained deeply enough that you go into every new book and every new source immediately interrogating the shit out of it?”

After asking the above questions alongside other questions, he concludes, “Being a historian is absolutely about reading books! But it’s not about reading them, it’s about critical analysis, discourse, argumentation, compilation. It’s critical reading and writing skills, absolutely, with a methodology and framework that takes time and training.”

In our current climate of distrusting and dismissing the very notion of experts, Thomas LaCaque’s twitter thread is needed. And while I am not a historian, I did study history during one my four stints in college and learned enough about historiography to become aware of my need to be cautious while reading history books; I know enough to know I don’t know enough. Take Coolidge by Amity Shlaes, for example.

I love reading biographies, possibly more than any other genre. A well-written biography can be as exciting and page-turning as the most enthralling novel while providing information and knowledge that helps me better interact with God’s creation in increasingly more holistic ways. Not counting autobiographies and memoirs, I currently own 75 biographies. Shamefully, only 13 of those 75 are biographies of US presidents. To remedy that, I determined earlier this year that when I buy a biography it will be a biography of a US president for the foreseeable future[3]. Not long after making that resolution, I found myself in Brightlights, a used bookstore near our house. Because Calvin Coolidge was one of the presidents I knew very little about, I bought the biography written by Amity Shlaes.

After finally pulling it off my shelf to read, one of the first things I did was to find out who Amity Shlaes is. Prior to Coolidge, I had never read anything by her and had never even heard of her. As LaCaque points out, it’s important to understand who the author is in order to spotlight biases and objectives stemming from worldview commitments. Well, a simple google search of Amity Shlaes reveals that she’s on the board of directors of the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation.[4] Red flag number one. Red flag number two for me is that it didn’t take much research to discover that her worldview is most decidedly (and consciously/admittedly so) that of classical liberalism. Now, and to be clear, none of those things preclude Amity Shlaes’ biography of Calvin Coolidge from being taken seriously, much less mean that anyone shouldn’t read it. Amity Shlaes is an excellent writer and historian; Coolidge is a valuable read. However, knowing what I know about her helps frame her framing of Calvin Coolidge. She’s interacting with him as an ally, not as a neutral party. There is no way to avoid the fact that this colors her perspective and, hence, book.

So, along the way, as I read Coolidge, I’d often take the time to research the events Shlaes chose to include and interpret in the biography. Reading counter-narratives and opposing viewpoints helped me keep the epistemological ship steered correctly – not perfectly, mind you.

I bring this up because God’s people should love truth and be diligent in the pursuit for truth. Blindly reading the first biography of Calvin Coolidge I found would not help me in the pursuit of truth.[5] Recognizing my own limitations helps me to proceed with cautious epistemic humility. Sadly, often owing to a lack of understanding about this more so than blatant hubris, many Believers interact with history books (and information and knowledge, in general) as if they have unfettered access to the truth. Most often, we do not. And when interacting with disciplines like history, science, math, theology, philosophy, etc., most of us have far less access to truth than we are aware or want to accept. Coolidge by Amity Shlaes is a well-written, informative book that serves as a reminder that we should approach all learning with humility and the desire to submit to the discipline’s rules of engagements, which requires us to know those rules of engagement. Otherwise, reading Coolidge comes with the high risk that I (or any reader) will walk away from the book unaware that my (our) perspective of President Coolidge has been shaped by a board member of the Calvin Coolidge Memorial Foundation.

By all means, read and read a lot, but read with a healthy dose of a hermeneutic of suspicion that encourages you to submit yourself to an appropriate epistemic approach. In other words, sometimes “doing the research” is not enough. You may very well lack the requisite understanding of how to appropriately interact with your research needed to legitimately form opinions and/or beliefs about the subject you’re engaging.

Don’t Forget the Compassion in Compassionate Conservatism

Amity Shlaes does an admirable job of calling her readers to respect and appreciate Calvin Coolidge the man. By all accounts, and not just Shlaes’, President Coolidge was a kind, thoughtful, and generous man. Referencing “Proper Historiography” from above, I’ve done my due diligence having read contrary reports/articles that argue for Coolidge’s role in the Great Depression as well as (and related) his aberrant policies (from the viewpoint of the authors – a viewpoint that I sometimes agree with and sometimes disagree with). I’ve also read “hostile” reviews of Shlaes’ book. All in all, though, a streak of admiration for Coolidge as a man runs through even his fiercest policy critics. However, I believe that his unwavering loyalty to classical liberalism created a severe blind spot that unfortunately often caused him to place Image bearers in subjection and service to policy. Jesus’ retort that Sabbath was made for man and not the other way around sprang to my mind as a tangentially helpful touchstone while reading the biography. In fact, that touchstone speaks to my umbrella concern with classical liberalism: it’s inability, ironically, to separate the individual from the equation.

In a well-known quip, Churchill observed with a truthful paradox that democracy is the worst form of government except all the others. I believe the core of Churchill’s sentiment applies to democracy’s philosophical foundation of classical liberalism, too.[6]

Classical liberalism is a human-made system. In and of themselves, human-made systems are not wrong. Way back in the Garden of Eden, God commanded Adam and Eve to create culture. Doing so necessarily entails creating and crafting systems that are, by definition, human-made. It’s not an insult for an ideology, political theory, scientific hypothesis, etc. to be tagged human-made. Problems arise, though, when we fail to properly place ourselves within God’s Story of redemption. After God gave our first parents that command, they rebelled and brought down God’s just and righteous curse upon all of creation. Now, living post-Fall and pre-eschaton, we create and craft while burdened by the Curse. This doesn’t mean that we are to sit in the corner wringing our hands in fatalistic desperation as we wait for King Jesus to return. Kingdom ethics call us to serve our communities, both broad and small. But living when we do also requires epistemic humility; acknowledging that our efforts are flawed and hampered by our own finiteness and sin is important. This is why it is of the utmost importance that we hold all human-made systems lightly and with a humility that desires and seeks out correction. Unfortunately, though, we tend to elevate our preferred ideologies, philosophies, political/economic theories to an unearned/undeserved position of unassailable, often to the point of turning them into infallible gods before which we bow. Even if we resist full scale idolatry, we tend to have blind spots that prevent us from seeing how our preferred way of “creating culture” damages and hurts God’s creation, including the pinnacle of His creation – Image bearers. One of the biggest blind spots of classical liberalism is that it tends to reduce humans to a variable within an equation. Take economics, for example.

Capitalism is the economic theory at the center of classical liberalism. Many of Coolidge’s policies were driven by the libertarian view of economics first formulated by Jeremy Bentham and his famous student John Stuart Mill. Prior to their embrace of a quasi, inarticulate mercantilism led by Donald Trump, Coolidge’s economic theories and policies were at the core of the GOP and the conservative movement. If you doubt me, I encourage you to read Russell Kirks’ masterful book The Conservative Mind. If that’s not enough to convince you, humor me by allowing me to engage in a touch of the logical fallacy of argumentum ad verecundiam, colloquially known as appeal to authority.

In brief, I have the privilege of knowing several men and women who engage the federal government at the highest levels; men and women who are avowed conservatives, many of them having studied economics formally. Whether they agree with my overall thesis or not, they will back me up when I say that Coolidge’s economic theories and policies, which are same theories and policies at the core of the historic (pre-2016) Republican party, are derived from Bentham’s and Mills’ reworking of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. Where they may disagree (although not all do, having discussed this very thing with them), is that Bentham and Mills shouldn’t have mucked up Smith’s application of his moral theories to his economic theory – actually, vice-versa;[7] Adam Smith believed that economics should be subservient to moral theory (ethics). Unfortunately, thanks to Bentham and Mills and their heirs (Ludwig Von Mises, Carl Menger, Thomas Sowell, etc.) anthropology and subsequently ethics are now subservient to economics.

To help see this, I offer somewhat of a strawman, albeit a helpful one and one that is made up of far less straw than my friends will likely be willing to (openly – as in, during their appearances on FOX News) acknowledge.[8]

Several years ago, I had as a frequent conversation partner a man who is more committed to classical liberalism than any other person I’ve known. More intelligent and better read than me, this man knows classical liberalism thoroughly, including capitalism. In conversation/argument with him, he’d often make the infuriating (to me) claim that people are only worth what they can produce. His argument was based on the validity of the law of non-contradiction applied to economic theory – as in, his beloved libertarian capitalism. If only people will do X, he’d insist, then Y and Z will occur. Meritocracy is dependent on the validity of the law of non-contradiction to libertarian capitalism.

Unfortunately, as I would argue back, we humans are walking contradictions, and this doesn’t even take into account the seemingly infinite (emphasis on seemingly) variables that are impossible to control for when interacting with economic theories. Out of all the soft sciences, economics is the softest.[9] And this is possibly the largest blind spot for libertarian capitalism.

Yes, any good working economic theory should account for things like how wealth is created and best distributed (via the invisible hand or the polis, by way of two competing examples), but it also should account, as best it can, for greed, avarice, differing levels of competence, acts of God (natural disasters, etc.), human fallibility, unforeseen obstacles, limitations of church, city, state, and even the federal government, among other many other variables that are difficult, if not impossible, to control for. In truth, for Christians, the greatest and second greatest commandments should be the starting and finishing point when interacting with all ethics. “Does this serve others or myself?” should be a controlling question when thinking through economics. “Does this aid the privileged while furthering oppression and suffering or does it ask the privileged to surrender their so-called ‘rights’ in order to fight oppression and suffering?” is another important ethical question to ask. Unfortunately, for all his personal integrity, President Coolidge was more devoted to serving a system than he was to serving fellow Image bearers.

In the final year of his presidency, Calvin Coolidge watched as his beloved home state of Vermont (where he was born and raised) suffered under the devasting effects of a cataclysmic flood. Apart from personally donating to the American Red Cross, the President of the United States of America did as little as he could to help because he was chained to a system of thought that believed that it was improper for the federal government to insert itself into what he believed was a state issue. “Rescue work was for the state governments.”[10] While personally heartbroken over the pain and devastation, a man who had the power to ease that suffering did very little because he was more devoted to a political theory than to loving his neighbor.[11]

Here’s where the rubber meets the road: my staunchly conservative friends will argue that the precedent of federal intervention ultimately causes more harm than good. I push back on that by pointing to the moving target that is human behavior; predicting the future based on political and economic theories is often fools gold. More importantly, Kingdom ethics call us to do what we can to ease human suffering. A cost benefit analysis of the present known good versus any possible future bad should be weighed. I’m not arguing that all prudence and caution be discarded. I’m pleading with conservatives to emphasize compassion even if that means sacrificing some of their defined conservatism. Jesus’ admonitions that Kingdom ethics look like giving our cloak to a needy neighbor and walking the extra mile should be the primary driver of our decisions and not the goal to adhere to political/economic theories. Before concluding, I’m going to provide one more example, an example I’ve confronted many of my conservative friends with.

During the latter half of 2004 and the first half of 2005, I worked third shift at a Home Depot in Antioch, CA. During my year there, the call came from Atlanta that the profit margins weren’t high enough in this particular store; shareholders were not seeing the return on their investment they expected. Within the framework of capitalism, I understand this. With less returns on investment than expected, investors will invest elsewhere. This jeopardizes a business’s (Home Depot in this instance) ability to grow and provide jobs. I get that. But there’s something (namely Image bearers) missing from that equation.

Armed with his corporate marching orders, the manager of the store where I worked began cutting hours. Not mine. Third shift was exempted. I asked the manager how he could justify cutting people’s hours who were depending on every penny to pay their rent and buy food. He immediately countered that if they worked hard enough, they could become managers, too. Meritocracy articulated.

As he spoke, my mind went to Steve (not his real name), a man who faithfully and cheerfully worked in the plumbing aisles during store hours. A friendly man, Steve had obvious cognitive limitations. So, I asked the manager, “What about Steve? Are you telling me that he has the ability to become a manager?”

The manager was unable, or unwilling, to answer.

Surely, there is a way to encourage investments while also providing resources that allow people like Steve to flourish in a system that only rewards those who can navigate the meritocracy. Safety nets are not enough; Steve, and others like him, should be allowed to taste of the fruit of flourishing that you and I do. Much of our privilege is not of our doing; likewise, much of Steve’s limitations are not of his. Why should you and I be rewarded while Steve suffers?

You see, placing economics (capitalism, in this case) above ethics requires adopting rubrics like the law of non-contradiction. It also requires embracing meritocracy. The problem is that economics is ill-suited to account for many of sin and sin’s Curse’s effects on people and the world we live in. Steve did not “earn” his cognitive inabilities any more than you and I “earned” our cognitive abilities that allow us to “pull ourselves up by our bootstraps” far higher than Steve ever can. To that end, the Coolidge quote at the top of this article should be seen as problematic for Christians. The government – including the federal government – should be in service to the people and should help serve as a means of justice, including fighting against oppression and aiding in flourishing.[12] And if the people won’t miss the federal government when it’s “gone out of business,” then it’s not serving the people in ways that help them flourish. When those working in the federal government prioritize Image bearers over political theory, the ethics will change.[13] They will actively seek for blind spots instead of circling the wagons. In doing so, they will be open to evolving and changing as the Curse’s effects on Image bearers are seen.

Emulate Calvin Coolidge’s decency but do so without being chained to a human-made ideology like he was. No human-made system is infallible, and no human-made system is immune from the effects of the Fall. If your preferred political/economic theory pits relieving the immediate suffering of Image bearers versus the protection of the system, that political/economic theory may very well have a blind spot that is causing you to violate Kingdom ethics. At the very least, loving God and our neighbors demands that we explore that possibility. It also includes the possibility that maybe, just maybe, we need to rework, and possibly discard, our preferred political/economic theories. Our mission is eschatological and not temporal. Working towards the furtherance of God’s Kingdom will frequently be at odds with those working to build earthly kingdoms. That conflict and tension should be felt by God’s people, and if it’s not, we need to be willing to ask ourselves if we’re worshipping something other than the Creator.

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] I’m neither a Republican nor a Democrat, so I don’t really have a dog in the two-party fight.

[2] His entrenched anti-regulation beliefs and policies helped create the entrance ramps to Wall Street’s irresponsible pedal-to-the-metal speculations that were arguably the main cause of the Crash in 1929.

[3] I may or may not have already violated this self-stricture. It’s the intent that counts, though.

[4] In fact, I didn’t even have to google it. The dust jacket proudly declares Shlaes’ involvement with the CC Memorial Foundation.

[5] I’m not saying that Amity Shlaes lied – far from it. I believe that what I’m trying to communicate is obvious, but to make sure I’m not misunderstood, I’m spelling it out in a footnote: two things can be true at once. It can be true that Shlaes was diligent and faithful in writing her biography, trying her best to be objective. But it can also be true that her own biases and ideological commitments prevent her biography from painting the whole picture of Coolidge and his presidency.

[6] Just to get this off my chest: It’s quite annoying every time some smug “lover of history” spouts, “The U.S. of A. is a republic not a democracy.” Yes, we all know that. However, smug “lovers of history” obviously do not understand how language works or philosophy in general.

[7] It’s important to point out that Adam Smith, as preferrable as I believe he is to Bentham and J.S. Mill, needs to be held loosely, too.

[8] First an appeal to authority and now a straw man? Maybe this article should be turned into a drinking game: drink a shot every time I commit a logical fallacy.

[9] It never ceases to amuse me how many of those who dismiss sociology and psychology for being soft science will quote Thomas Sowell as if he’s infallible.

[10] Amity Shlaes, Coolidge (New York: Harper Collins, 2013), 358.

[11] That wasn’t the first time. Earlier that year, apart from sending Herbert Hoover armed with surplus military tents, supplies, etc., Coolidge did nothing when a flood devastated the Mississippi valley.

[12] Government was instituted by God in the Garden of Eden. It’s not the result of a damnable social contract. As such, government should seek to represent God. … Granted, since the Fall, things are all out of whack and governments are self-serving. And all this raises questions about Christians involvement (and how much/deeply) in earthly governments – questions outside the scope of this article.

[13] It should be noted that the notion that churches should be responsible for things like health care/hospitals in the age of MRI machines is preposterous. Thank about the immense expense of modern medicine versus hospitals in the 19th and previous centuries. Pointing to churches that built hospitals generations ago is anachronistically unhelpful and unrepeatable in the 21st century. The federal government, however …

I appreciate the thoughts on historiography. The believer should read to understand the world better, not to claim any internal authority bestowed by reading someone else’s opinions on historical events.

I’ve been reading biographies of the presidents in order. (On Grover Cleveland now). I wish I would have done this a while back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I contemplated reading biographies of the presidents in order but decided to start with the books/bios I already have. I wish now, though, that I was reading them in order.

LikeLike