by John Ellis

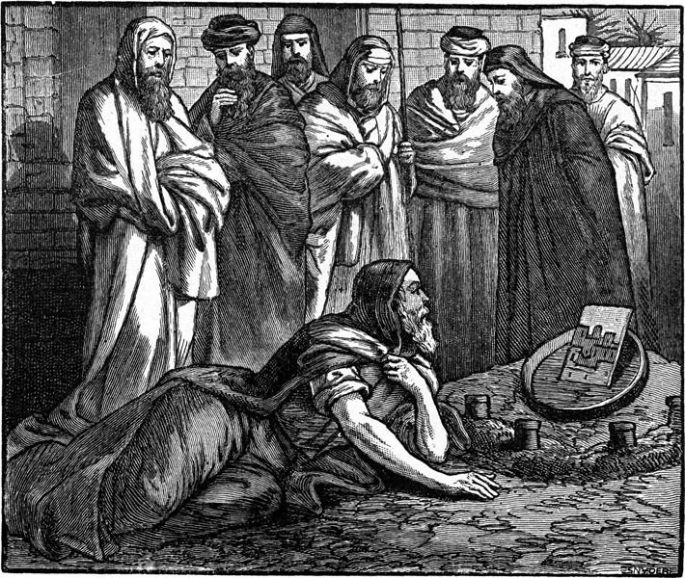

The prophet Ezekiel was the first experimental theatre artist. The oft-lauded, ancient Greek theatre gurus commercialized theatre.

Maybe.

To be honest, I can’t prove that the Greeks read the Old Testament prophets and then bastardized Ezekiel’s theatre theory; nor can I prove my claim that Ezekiel was the first experimental theatre artist. Nor does proving either matter for my point. What is demonstrably true is that Ezekiel, under the divine direction of God, performed theatre in ways that melded the world of imagination with the world of reality, creating a form of confrontational theatre that was vivid and frightening. And a form of theatre, frankly, that was outside the recorded norms of storytelling for that time period (or any time period, for that matter). The Greeks, on the other hand, produced theatre that appealed to the populace at large – pop theatre, if you will.

As John Russell Brown points out in The Oxford Illustrated History of Theatre, for Greek theatre, “An audience number of 14,000 has become canonical; but it might have been possible to cram in something more like 20,000.”[1]

Ezekiel, on the other hand, performed for passerbyers.

I’ve long had the desire to perform Waiting for Godot as a busker. Standing on a street corner, my fellow storytellers and I would seek to engage passerbyers. To do so would require someone, anyone, just one person, to stop passing by and enter into the story with us. The world of reality would enter into an intimate relationship with the world of imagination.

The main difference between my hypothetical performance of Waiting for Godot and Ezekiel’s Divinely written, produced, designed, and directed dramas is that Ezekiel used imaginative forms to relate true stories to his audience. Waiting for Godot, of course, is a work of fiction; brilliant fiction, to be sure, but fiction nonetheless. The core, however, is the same: an actor asks an audience to enter in to the storytelling experience with him. Doing so taps into the one of the universal aspects of humanity: we’re all created in the Image of God, who is the eternal and sovereign Storyteller.

Theatre (storytelling) is the Christian’s birthright. Sadly, that birthright has been watered down and sold for cheap entertainment. That’s not to say that there aren’t Christians who are attempting to reclaim our storytelling birthright. It’s that the forms often fall short of Ezekiel’s template of intimately engaging the audience. Pushing the boundaries of the craft is generally anathema in storytelling forms that boast “Christian” as an adjective.

A while ago, I wrote an article for a website about the Erwin brother’s latest project called Kingdom, a collaborative Christian filmmaking company. If you’re unfamiliar with Andy and Jon Erwin, they’re the creative force behind the movies Woodlawn, Mom’s Night Out, October Baby, and the smash hit I Can Only Imagine which grossed almost $90 million at the box office against a budget of only $7 million.

On the strength and financial windfall provided by I Can Only Imagine, the Erwin brothers hope to create a Christian filmmaking company that will be able to rival Hollywood’s secular studios. It’s an ambitious project, and I wish them well. While writing that article, though, I couldn’t help but think of my own desire to see a collaborative theatre a la the Group Theatre of the 1930s. The big difference between me and the Group Theatre, of course, is that I want to see a theatre rooted in Kingdom ethics and populated by followers of Jesus who are also theatre artists striving to tell stories that we believe in and believe.

Like many theatre artists, Harold Clurman was one of the theatre theoreticians to whom I looked for guidance; a theatre voice who captivated me and provided me a loose blueprint for my theatre vision. He wasn’t the only voice, of course, but an important one in my evolution as a theatre artist. He was also the co-founder of the famed Group Theatre and was the Group’s driving artistic force throughout its brief existence.

Apart from our worldview level ideological differences, I share Clurman’s belief that, “A real theatre exists when a group, united by a common aim, works together to give the most complete dramatic expression to the ideals that inspire it.”[2]

The problem is that although I believe Clurman’s wisdom to be true, I’m not sure that it’s possible. At least not if attempted within the framework of his worldview, which is the worldview of most theatre artists.

Sadly, yet predictably, the Group Theatre was notoriously undone by clashing visions that grew out of clashing egos. I believe that a collective of Christian who are theatre artists and who are committed to serving God first, serving others second, and thinking about themselves last would have a greater chance for success than secular artists still dominated by the sinful desire to build the Tower of Babel.

The potential hiccup, though, is that while Christian theatre artists possess a unifying worldview that encourages selflessness (if not demands it), they also lack a unifying aesthetic tradition that allows for experimentation. In fact, in my experience, any attempt to prod Christian theatre away from the traditional is met with great suspicion. The Christian experimental theatre artist is forced, in many ways, to operate in an aesthetic vacuum.

Although not “experimental” in the way the word is generally defined in the 21st century, while pushing theatre boundaries and challenging storytelling norms, the Group Theatre had the luxury of not existing in an aesthetic vacuum; its founders and principal actors were greatly influenced by the Moscow Art Theatre and the teachings of the MAT’s founder Constantin Stanislavski. In turn, Stanislavksi had been influenced by the great 19th century Russian serf director, actor, and theatre teacher Michael Shchepkin. He stood on the shoulders of others, Goethe and the Weimer Theatre, for example, and on and on, through Francois Delsarte and continuing through an evolving line of influences until we reach the original actor Thespis, who, no doubt, learned a thing or two from the Egyptians. A theatre tradition that spans over two and a half millenniums.

Although Christian theatre artists stand uneasily in the larger theatre tradition, there is sadly no distinctly Christian artistic through-line-of-action formed and reformed in the stream of distinctly Christian theatre companies (not to mention experimental Christian theatre). Considering the Prophet Ezekiel, this fact takes on an even sadder resonance. There should be a Christian artistic through-line-of-action.

To make matters worse, over the years I have heard many professing Christians dismiss the notion that it’s possible for artistically excellent Christian theatre companies to exist. True, the most obvious representations of Christian theatre (Sight and Sound, for example) are little more than campy, overly didactic productions that feel as if they belong on a cruise ship or in a theme park. But the absence of a Christian theatre tradition that tells stories in compelling and aesthetically excellent ways does not mean that it’s impossible. It does mean, I think, that the artists involved in such an endeavor have a lot more initial heavy lifting to do in weaving together a robust orthodox Christian worldview with theatre theory.

Setting aside for the moment the all-important theology aspect to briefly focus on theatre theory, my experience tells me that collaborative efforts demand a ground-level unanimity. Unless those in the company who shape the direction agree on the core theatre theory, the whole endeavor is doomed to fail. Clurman, who knew a thing or two about how collaborative theatre can collapse in on itself, warned, “The theatre is a collective art, which is not the same thing as an accumulation of artistic contributions.”[3]

I’m afraid that true collaboration the way many define it isn’t possible. What’s probably needed is an individual with a strong understanding of theatre theory, a distinct vision growing out of that understanding, and a personality that can challenge, teach, and lead others without wounding them. Shaping and guiding the collective work needs more than a guiding philosophy. It needs a guiding hand, too.

For what it’s worth, I also believe that the audience shouldn’t be treated as consumers but as collaborators. That requires humility on the part of the company, a trait frequently lacking in theatre artists.

The vision must include more than a philosophy of how to make theatre. A clear vision of what the company wants to say is a must. To put it another way, a clear vision of what kind(s) of conversations the theatre artists want to have with the audience is a must. And this is where theatre theory and worldview (theology) intersect. For example, Christology shapes the nature and communication of a church’s worship service. To use more technical terms, form and function are not just guided and shaped by theology, they’re intimately connected. And, frankly, vice-versa.

This means that for a Christian theatre company to work well, or at all, for that matter, the principle artistic voices must swell in unbreakable unison as the company works through those aesthetic decisions that are guided first and foremost by theology. I don’t think that requires unity over certain denominational distinctives. I do believe, however, that it requires non-negotiable unity over the fundamentals of the faith. For me, agreement over the Five Solas would be a good starting point.

This has been just the tip of the iceberg. Having studied theatre theory, thought through all this, and having already put many of my thoughts into practice, I have strong beliefs about how a Christian theatre company should operate and what its guiding principles should be, both theology and theatre wise. To that end, this is the first of three articles. In part two, I will deal specifically with the worldview (theology) of a Christian theatre. Part three will deal with theatre theory. A fourth article may be needed to integrate parts two and three and articulate a concise vision for Christian theatre. In the meantime, if you’re a theatre artist, I hope this article inspires you, even if you have points of disagreement. If you’re not a theatre artist, I hope this article causes you to be curious about the ancient art of enacted storytelling and how Christians can better utilize that art for the glory of God and the spread of His Kingdom.

Soli Deo Gloria

[1] John Russell Brown, The Oxford Illustrated History of Theatre (New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001), 18.

[2] Harold Clurman, The Collected Works of Harold Clurman: Six Decades of Commentary on Theatre, Dance, Music, Film, Arts and Letter ed. by Marjorie Loggia and Glenn Young (New York: Applause Books, 1994), 144.

[3] Clurman, The Collected Works of Harold Clurman, 329.

4 thoughts on “A Christian Theatre Manifesto: Part 1”